World Nutrition

Volume 3, Number 7, July 2012

Journal of the World Public Health Nutrition Association

Published monthly at www.wphna.org

The Association is an affiliated body of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences For membership and for other contributions, news, columns and services, go to: www.wphna.org

Commentary: The best food on earth

Peru: As good as it gets

Enrique Jacoby

Regional Advisor, Healthy Eating and Active Living

Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC, USA

Email: jacobyen@paho.org

Click here for member's profile

Access pdf of this commentary here

Preface

Colin Tudge writes: There is a wondrous serendipity in the whole food story. This is that good farming, based on enlightened husbandry, provides the kinds of foods that are nutritionally perfect, and which support the world's great cuisines. In short, if the world took its lead from good farmers and good cooks, and if science was content to serve these traditional crafts, humanity would have nothing at all to worry about.

How does modern nutritional advice fit in with the demands of good, benign, sustainable husbandry? Like a hand in a glove, is the answer. When the land is treated well, it produces variety. A variety of plants and animals, working in harmony, is needed to bring out the best in it. In general, plants would prevail, with staples dominating and a patch of vegetables at every opportunity. But there would always be some animals.

How, then, would this combination of sound nutrition and enlightened farming match the demands of gastronomy? Absolutely perfectly, is the answer. Every country – and where tradition prevails every region and every village in every country – has, or has had, its traditional cooking. Some is clearly better than others. In my book So Shall We Reap (1) I said: 'Few would dispute that among the supreme masters are Italy, France, China, and the Arab-influenced countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Others would bid for Turkey, some for Mexico'. In introducing the first in this enlightened World Nutrition series on 'The best food on earth', I am delighted to add Peru to this list.

In a piece for Public Health Nutrition a little later (2), I wrote: 'Skills developed over many thousands of years , especially in farming and cooking, demonstrably can do all that the world requires. Hope lies in creating conditions in which evolved traditional skills can develop further'. I also wrote: 'Traditional cooking, rooted in the home, contains the answers to all the world's prime woes: the need for good nutrition, agreeable social life, and autonomy. It needs to be encouraged everywhere'. I raise my glass to the farmers, fishers and cooks of Peru. I raise my glass to Enrique Jacoby in his work for the Pan American Health Organization, encouraging healthy eating with all this really means, throughout Latin America.

Introduction

Editor's note

This is the first of an occasional WN series on great cuisines of the world, usually written by Association members. The focus will be on cuisines which, like those of the Mediterranean region, and those from India, China and Thailand, have gradually evolved out of the prevailing climate and terrain and from indigenous and established plant and animal sources, as everyday and feast food of the people. Just as 'nutrition' can mean nourishment of the mind, heart and spirit as well as of the body, 'cuisine' in this series is taken to include healthy nutrition in the conventional sense, as well as referring to long-established and traditional food systems, commensal pleasure, and gastronomic delight. We use the term 'diet' here also in the classical sense, of the good life well led, of which food systems are a central and treasured part. Enrique Jacoby is Peruvian. He works for the Pan American Health Organization, and recently was seconded for a while as Peru's national deputy minister of health.

In the dozen years so far of this century, the traditional food culture and cuisine of my country of Peru has gained a global reputation. Here is what a travel writer says in a leading in-flight magazine this month of June (3) as I write: 'Peruvian is the new Mexican. The South American country's mouthwatering cured-fish ceviches, spicy mashed-potato causas and tender alpaca steaks – though possibly not its roasted guinea pigs - are going global. Native chefs such as Virgilio Martinez,of Central restaurant in Lima and of the forthcoming Lima London in Fitzrovia, are reworking the nation's classic dishes and its cornucopia of fresh ingredients for gourmet palates. International gastronomes such as Denmark's René Redzepi and Spain's Ferran Adrià sing the praises of Peruvian food, and Peruvian restaurants are springing up across the Americas, Spain and London'.

But I may already be given a wrong impression. This commentary is not about gastronomy for rich people who can afford to travel across continents in search of new exquisite tastes, like the ancient Roman rulers. I am writing about gastronomy of the genuine type, which is the quintessence of the long-evolved traditional farming and food of the people. In the case of Peru, these are a wondrous mixture of descendants of Incan and many other native races, and of the Spanish conquerors who came half a millennium ago, together with people who came from Africa, and later from the entire Mediterranean region, and also from China and Japan. This rich mix of peoples is one explanation of the glory of Peruvian fishing, farming, food preparation and cooking, and of our commensal family-centred ways of life.

Box 1

Peru in brief

Peru, a republic since July 1821, is the third largest country in South America, with an area of the UK, France and Germany combined. See map above, right. Almost one-third of its 30 million people live in the coastal capital of Lima. What is now Peru was the centre of the highly developed Inca civilisation and empire, which in the 150 years before the Spanish conquest stretched along the whole Andean region that now also includes Bolivia, Ecuador, much of Chile, and part of Colombia and western Argentina. See above, left.

Peruvian food systems, and its traditional and more recent food culture and cuisine, are functions of climate, terrain and history. Despite the subjugation and reduction of the native peoples after the Spanish conquest, original influences and customs, including food systems, survived, and about four-fifths of the population is of mixed native and European blood, or native. Peru's astounding terrain includes the Pacific Ocean, a relatively arid coastal strip, the Andean highlands with peaks of over 6,000 metres, and Amazon rainforest. Thus Machu Picchu, Peru's most celebrated highland Inca site (picture below) became known internationally only a century ago.

Although Peru is tropical, the climate is cooled by the oceanic Humboldt Current and rivers flowing from the Andes. The variety of Peruvian terrain and climate accounts for a staggering biodiversity of plant and animal life, estimated at over 20,000 species, that also has largely survived.

The glory of Peruvian food

The first South American country to achieve world gastronomic status is my own country of Peru. Note please that I say 'South American', because Mexican cuisine has been established internationally ever since the time 200 years ago when Thomas Jefferson purchased what are now the states of California, New Mexico and elsewhere from Spain. But South America is south of Panama.

Gourmets all over the world have known for decades that Peruvian cuisine is special, as indicated by Felipe Rojas-Lombardi's classic cookbook published over 20 years ago (4). Also, the classic dishes of other South American countries such as Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina, not to mention those of Caribbean and Mesoamerican countries, are now internationally celebrated, and important tourist attractions.

There are overall reasons why everyday food as well as feast food in some countries and territories is so delicious, which help to explain why I am writing this commentary for a journal concerned with nutrition and public health. One reason is that the great cuisines of the world typically have been evolved over very long periods of time, and originate with everyday meals and dishes that make the best use of available foods and ingredients suitable to the local climate and terrain. Another reason, which follows from this, is that gatherer-hunters, pastoralists and peasant-agriculturalists develop deep knowledge of what diets and foods sustain life itself, with adequate dietary energy, and also preserve health and protect against disease. A third factor, which is one of the reasons why Peruvian cuisine is extraordinary, is the mix of cultures that comes about as a result of invasions and migrations.

So what is so special about Peruvian food, and why? Its eruption on the global stage has been bubbling under during the last two decades. Now a whole new cohort of adventurous chefs, of which the best known is Gastón Acurio (featured on the cover of World Nutrition this month) have made Peruvian cuisine fashionable throughout the world, with restaurants opening in many major cities. The change has been felt in Peru itself, where French and Italian cuisines have long been the preferred options when it came to a banquet in high social and political circles. Now though, it is Peruvian cuisine that is being preferred in Peru. High-ups are well aware that Peruvian gastronomy at home as well as abroad is becoming a big tourist attraction. Loyalty to the sabor nacional (the national taste) is spreading.

Andean agriculture and food systems largely predates Spanish conquest, but the current story takes a new spin after the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire, almost 500 years ago (6). Spanish conquerors, mostly from Andalusia, were introduced to an almost infinite array of new foods (among them potatoes, peanuts, beans, corn, chili peppers, quinoa, unknown fish), which have been subject of numerous historic and nutritional studies (7) and the local Andean culinary. In the ensuing five centuries, Andean, Iberian and Arab cooking traditions amalgamated into what was later know as Peruvian food. The story is told in a little more detail here in Box 2.

Box 2

The origins of Peruvian cuisine

This is adapted with many thanks from 'The history of Peruvian cuisine', obtainable at: http://www.culturalexpeditions.com/culinary_history.html.

Peruvian food culture begins with the Incas and the pre-Inca civilisations. It then developed as a result of the mixing of indigenous traditional and long-established food systems with Spanish traditions. Later rich mixtures came about as a result of migrations from Africa, Europe outside Spain, China and Japan.

Incan food culture

In the Mesoamerican Mayan culture corn, as the staple source of life, was revered as a god. Corn also remains specially valued in Incan culture and thus in Peru

At the time of the Spanish conquest, contemporary chronicles describe Incan food systems and culture. A sign of the success of the Incan empire was abundance of food for communities of all classes. As in Mexico, corn (maize) of many varieties – see above – was a valued staple food, prepared toasted or boiled in water or prepared into tamales.

The potato originally comes from the Andean region. This was also a basic ingredient, cooked or roasted and used in stews. Also used were squash, a variety of beans, and yams. Animal foods included llama, alpaca, guinea pig, and other game or domestic animals, a great variety of birds, and especially fish and seafood. Before the Spanish conquest it was estimated that about a third of the coastal population was dedicated to fishing for the vast variety of fish in the Pacific Ocean. Fruits included avocados and pineapples. There are in Peru many other very popular varieties of fruits, vegetables, tubers and cereals that are not known outside, such as lúcumas, tunas, granadillas, huacatay, caiguas, ollucos, kañiwa.. Quinoa and amaranth were important foods before the conquest, as well.

After the conquest

The Spanish conquest brought with it wheat and rice; leafy vegetables and salads, garlic, olives, onions, grapes, oranges, limes, apples; cattle, poultry and rabbits, and many other foods. Equally important, it brought Spanish food culture and cuisine. Sugar made possible the vast variety of desserts. During this period, many Spanish recipes incorporated native ingredients such as corn, yams, potatoes, and yucca. The Spanish also brought with them African slaves. African influence proved essential to Peruvian culture, particularly regarding music and cuisine.

Oriental influence

Between 1850 and 1875 around 100,000 Chinese immigrants arrived in Peru. as cheap labour, mainly to work in cotton and sugar-cane plantations. They conserved their cultural identity and traditions, and many moved to Lima. They opened small eating places, and introduced new frying techniques and ingredients like soy and ginger. There are now around 20,000 Chinese eating places in Peru. This has created the third most important element in the mix that makes modern Peruvian food culture and cuisine. In Peru now, every market includes Chinese ingredients. Japanese immigrants began to arrive at the turn of the century. Their restaurants served delicious fish and seafood dishes and helped shape what is now the world-famous Peruvian ceviche (see Box 3).

The food and economic boom

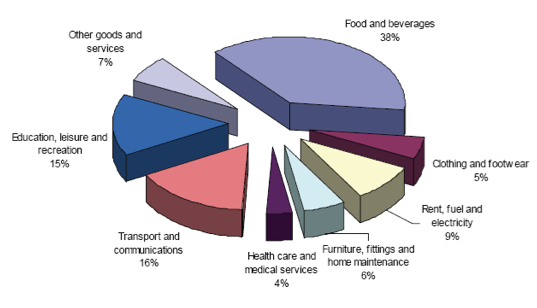

The Peruvian cuisine boom has serious economic figures attached to it. The hotel and restaurant industry has grown from 3.9 per cent of national gross domestic product in 2000 to 7.6 per cent in 2006, of GDP in the year 2000 to 7.6% in 2006, and employment in restaurants and bars grew a staggering 39 per cent from 2001 to 2004 (7). Tourism figures are in the same track, and a growing number of tourists are now opting for gastronomic tours instead of the typical trip to the Machu Picchu ruins near Cusco. Peruvian food abroad is also making big strides. Cities like Barcelona, Madrid, San Francisco, New York, Mexico City, São Paulo and Buenos Aires host today top notch Peruvian restaurants that compete with the best in town. All those restaurants together, according to some estimates, are now grossing 1.5 billion dollars a year. All this is in the context of a country that loves food. Figure 1 below shows how: in Peru almost 40 per cent of income is spent on food and drink.

Figure 1

Spending on food and drink in Peru

Source: Economic Forum. Global Economy Analysis and Report. August 2011

The boom, forecasts Peruvian anthropologist and chef himself, Mariano Valderrama, board member of the Peruvian Association for Gastronomy (second from the left in the picture below) will have a far reaching impact . It will positively influence the quality of home and street food, and will add value to the country's food supply chain, creating a greater demand for a myriad of traditional foods, ingredients, herbs and new products.

The anthropologist and chef Mariano Valderrama (second from left) sees

Peruvian cuisine as fundamental to the country's identity and its future

Peruvian cuisine has also stood the test of time as it nurtured and nourished several dozens of generations of Peruvians. Quite an accomplishment when compared to the wreck of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer seen in other countries in the last two generations.

Tradition and health

The Peruvian Ministry of Health's slogan Eat tasty, eat healthy, eat Peruvian was inspired by the current culinary boom and its force to inspire social change. A group of people who met at the Ministry of Health of Peru last December came up with the slogan after identifying Peruvian foods as having valuable characteristics, some commonly overlooked by nutritionists. A wide variety of natural (whole) foods are the basic ingredients of traditional dishes loaded with superb taste. Peruvian food culture and cuisine is based on locally grown food and also an intense regional exchange. It involves an active participation in food preparation (whereas processed products are automated and standardized). And Peruvian food ways are commensal: food is shared around tables, and so has a symbolic and cultural dimension. They give health and vitality in many ways in addition to protecting against diseases.

The idea of taking traditional foods as a guide to healthy eating is not new. The Mediterranean and Japanese food traditions, after being meticulously studied, have turned into global examples of healthy eating and the key to long and healthy lives. Not all food cultures have received similar scientific scrutiny, but without a doubt all have stood the test of time that runs well over millennia.

What most, if not all, of them seem incapable of achieving on their own, is to withstand the market muscle of ultra-processed products industries. These have gained significant influence on agriculture priorities, trade and government subsidies under the mantra of quantity over quality, and sell convenience by leaving cooking behind. They employ marketing budgets of $US billions to brainwash customers by infusing in their products an image of coolness and health.

Mexico: the warning

For us in the Americas, Mexico is the warning. In just about one decade Mexico turned into the world number one market for Coca Cola, overtaking the US. Consumption of sugary drinks jumped 40 per cent in the general population and 60 per cent among the poor; whereas consumption of fruits and vegetables and beans went down by 30 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively. In 2011 the Mexican government announced that the country has the highest rates of childhood diabetes, and of obesity, in the world. Was this just sheer coincidence? No, certainly not.

During the preceding 10 to 15 years, the celebrated Mexican food traditions, particularly those alive in family kitchens and tables, local markets and farms, were overpowered by the penetration of industrial food systems. This left Mexicans with almost no social tools or infrastructure to keep their food traditions running at home. Agriculture ended up benefitting big agribusiness. International trade favoured foreign imports. Ultra-processed products reaching even the most remote areas of the country with their products. Sure, Mexican haute cuisine is still booming, but the culinary traditions from which it originally derived are being destroyed.

Government action in France

The French, on the other hand, started to worry about the rise in childhood obesity in the 1990s –a modest rise compared to the US and Mexico-- and the invasion of fast food. At one point, Paris was the city with the highest concentration of McDonald's outlets in the EU. The preoccupation took the form of a deep concern on the many threats facing their food culture.

What followed was a major public overhaul of the French food system. The government banned vending machines in all schools, made (without food industry involvement) school nutrition guidelines stricter, and implemented a soda tax. In addition, the government successfully requested UNESCO to add French gastronomy to its list of intangible world cultural heritage.

The school lunches served daily consist of freshly prepared four course meals. Children are discouraged from bringing food from home. The typical menu will be a salad as starter, the main course, cheese and dessert (most times fresh fruit). Fried food, ketchup and sweet pastries are served no more than once a week. During lunch, professional staff help children to taste and eat a variety of foods, encouraging eating only at the table during for at least 30 minutes. As for drinks, only water or milk, no sugary drinks are served.

Box 3

Ceviche

You can see why ceviche is often called the Peruvian sushi. The basic principle is the same. With ceviche, raw fish or seafood is marinated and thus 'cooked' by being soaked in the juice of limes. It's as simple as that. Thereafter, the only limit to the imagination of the cook or chef is what to add. In Peru, onion is usually added, and sometimes some chopped herbs. Substance and flavour contrast is commonly supplied by boiled potato or sweet potato or sweet corn. Here is just one of hundreds of recipes:

Classic fish ceviche

Adapted from a recipe in theperuguide.com

Ingredients

800g of white fish (sea bass, flounder, grouper, sole, other).

1 red onion, sliced finely

1 tablespoon ají limo (limo chili pepper), chopped very fine

Juice of 15 limes

¼ cup fish stock (optional)

Salt

Preparation

Slice fish into 2cm pieces and mix with the sliced onion.

Season with salt and the chili pepper.

Toss fish in lime juice and mix well.

Let for 5 minutes (until the fish turns very white).

Add the fish stock and mix well

Serve ceviche right away.

Accompany with boiled sweet potato, boiled corn. and lettuce.

Makes 6 servings

Conclusion

A country's food traditions offer a wonderful platform for good nutrition. They provide profound connection between the natural world, food, people eating at the table and cultural identity. But now that transnational industries are penetrating countries throughout the global South, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, it is unlikely that protection and promotion of healthy eating can succeed unless it is coupled with the creation of an infrastructure of healthy eating. This involves resisting the invasion of ultra-processed products, regulation and restriction of the advertising and marketing of such products, creating incentives to make whole food agriculture and allied markets, flourish and grow strong. That infrastructure provides the basis to build the common good in nutrition. This is something that the so-called 'free market' will never provide: its concern is short-term satisfaction of the individual consumer in order to maximise profits.

So can Peru withstand the onslaught? Almost without exception, countries undergoing the penetration of ultra-processed products made by transnational manufacturers and associated industries have suffered a quick and steady dismantling of whatever infrastructure existed in support of traditional cuisines and good public health nutrition. In my opinion, the tradition of Peruvian food culture, and the current boom of Peruvian cuisine, will not of itself be sufficient protection. It is for sure a necessary ingredient but not a sufficient one. What is critical –and sooner rather than later – is concurrently to build an infrastructure of healthy eating and wellbeing. This, I propose, is where public health nutritionists – and the World Public Health Nutrition Association – can help my country and what it represents.

References

- Tudge C. So Shall We Reap. The Concept of Enlightened Agriculture. London: Allen Lane, 2003.

- Tudge C. Feeding people is easy: but we have to re-think the world from first principles. Public Health Nutrition 2005, 8, 6A: 716-723.

- Curtis N. Peruvian food. High Life, June 2012.

- Rojas-Lombardi F. The Art of South American Cooking. New York: Harper Collins, 1991.

- Diamond J. Guns, Germs and Steel. The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton, 1997.

- History of Peruvian cuisine. Obtainable at: http://www.culturalexpeditions.com/culinary_history.html

- Antunez de Mayolo S. La nutricion en el antiguo Peru. Banco Central de Reserva 1981

- Valderrama M. El Boom de la Cocina Peruana. http://www.rimisp.org/FCKeditor/UserFiles/File/documentos/docs/pdf/DTR-IC/elboomdelacocinaperuana.pdf

Acknowledgement and request

Readers are invited please to respond. Please use the response facility below. Readers may make use of the material in this editorial if acknowledgement is given to the Association, and WN is cited. Please cite as: : Jacoby E. The best food on earth. Peru: As good as it gets. [Commentary] World Nutrition, July 2012, 3, 7: 294-306. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

I wish to thank Patricia Murillo, my wife, for her ideas, comments and editing work. Thanks also to Colin Tudge for his preface. This commentary has been developed by Geoffrey Cannon. Support has also come from Carlos Monteiro and Jean-Claude Moubarac and colleagues at the Centre for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

The opinions expressed in all contributions to the website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association (the Association) including its journal World Nutrition, are those of their authors. They should not be taken to be the view or policy of the Association, or of any of its affiliated or associated bodies, unless this is explicitly stated.