World Nutrition

Volume 2, Number 3, March 2011

Journal of the World Public Health Nutrition Association

Published monthly at www.wphna.org

The Association is an affiliated body of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences For membership and for other contributions, news, columns and services, go to: www.wphna.org

Correspondence

The big issue is ultra-processing

Access the pdf of the January commentary on bread here

Short communication

When calories are not calories

Sir: Our dietary choices affect how much energy (measured as calories) we burn as well as how many we consume. After eating a meal, our metabolic rate increases in response to digestive processes such as peristalsis, enzyme synthesis, and nutrient uptake and assimilation (1,2). This 'specific dynamic action' (SDA) of food has been well-known for a century, but curiously, study of the relative SDA of different types of diet has been neglected.

More refined foods (those heavily laden with added sugars and other processed carbohydrates), require less digestive energy than minimally processed or unprocessed foods, which often have more protein, are higher in dietary fibre, and have a greater nutrient density (3-6). So the given calorie content of a meal is not the actual amount of net calories the body receives. A 110 calorie sugared soft drink does not have the fibre, structural integrity, or nutrients of a 110 calorie apple, and thus will require less digestive work by the body. What this means, is that by their very nature, consuming ultra-processed food and drink products (UPPs) in place of minimally processed or unprocessed equivalents is likely to result in a greater overall caloric intake and an increase in body weight and body fat.

The idea that UPPs require less energy to digest is common sense, when one considers the processes of manufacture. Anything chemically altered, pulled apart, ground, heated, cooled, re-heated or moulded or extruded and then packaged, loses much of its original structure and molecular integrity. UPPs are in effect predigested, as grotesque an image as that might be. Essentially, the external energy-intensive industrial production system that makes refined ingredients and products, is displacing our own internal personal digestive system that is designed to break down food.

Until fairly recently, the metabolic consequence of eating UPPs was mostly conjecture. A new study has tested this theory by measuring metabolic responses to two snack meals differing in degree of processing but equal in calories. As defined in the recent WN commentary (5), both meals were of ultra-processed products, but one was more processed than the other. The study found that post-meal energy expenditure from digestion was nearly 50 per cent greater for the less processed meal than for the more processed meal (7).

The test meals were fed to 17 volunteers. They were both cheese sandwiches, one composed of wholegrain bread and real cheddar cheese ('less processed') and the other of highly refined white bread and processed cheese-product ('more processed'). Both meals were comparable in terms of protein, carbohydrate, and fat content. As shown in Table 1 below, the metabolic responses were strikingly different. The metabolic rate following ingestion of the less processed meal on average stayed elevated for an hour longer and burned nearly double the amount of meal calories than the more processed meal – both showing very high levels of significance.

Table 1

Metabolic response to a less processed

and more processed snack meal

| Metabolic response |

Less processed |

More processed |

p-value |

| Duration of increase in metabolic rate after eating | 5.8 ± 0.11* hours | 4.8 ± 0.23 hours | 0.001 |

| Amount of energy expended during metabolic response | 137.7 ± 14.1 calories | 73.4 ± 10.2 calories | 0.0009 |

| Per cent of meal energy burned in metabolic response | 19.9 ± 2.5 % | 10.7 ± 1.7 % | 0.005 |

*Values are average ± standard error

From outward appearance, these snack meals do not seem all that different, which makes the results even more remarkable. The results might be more dramatic if minimally processed or unprocessed foods such as fresh vegetables and fruits and beans, were tested against ultra-processed products.

If the findings of this small study are replicated, the implications are profound. Modern industrialised diets of the types now eaten by most people in many higher-income countries are dominated by pre-packaged convenience products. To combat this, standard nutrition advice has stated 'eat less', but maybe the correct advice is to 'eat more' of minimally processed and unprocessed foods, and give our bodies their natural work to do. Weight Watchers®, an international company offering dieting products and services, recently caught on to this by re-vamping their 'points system', saying: 'The new plan… is based on scientific findings about how the body processes different foods. The biggest change: All fruits and most vegetables are point-free… Processed foods, meanwhile, generally have higher point values, which roughly translates to: should be eaten less'. (8)

This is a huge change in emphasis for dieting regimes. It is no coincidence that the growing appeal of 'fad' and 'quick results' dieting regimes have coincided with increasing obesity rates (9). After all, products like 'Lean Cuisine Meals' and 'Snackwell Treats' are really nothing more than UPPs presented as health foods.

Richard Wrangham's book, Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, explores the link between human evolution and the advent of food processing (10). He proposes that Homo sapiens evolved because of the advent of minimal food processing techniques (such as grinding nuts and using fire to char meats and vegetables), allowing extraction of more energy from foods, and the diversion of more energy to brain development, among other things. If changing diets from unprocessed to minimally processed foods created a new species, what will the transition from minimally processed to ultra-processed foods do?

Over the past 30 years, the production and consumption of UPPs has sky-rocketed, and worldwide obesity rates have doubled (5, 11).This provides even more context to this discussion. Although it's true that ultra-processing is not the only cause of the obesity problem, understanding and reacting to the troublesome effects of UPP consumption will be a critical step towards fighting this global epidemic.

Sadie Barr

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore MD, USA

Email: SadieB.Barr@gmail.com

References

- Secor SM. Specific dynamic action: a review of the postprandial metabolic response. Journal of Comparative Physiology 2009; 179:1–56.

- McCue MD. Specific dynamic action: A century of investigation. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2006; 144(4), 381-394.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005; 81:341–54.

- Shahidi F. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: whole versus processed foods. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2009; 20:376–87.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. [Commentary] World Nutrition, November 2010; 1, 6: 237-269.

- Eaton SB. The ancestral human diet: what was it and should it be a paradigm for contemporary nutrition? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2006; 65, 1-6.

- Barr SB. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food and Nutrition Research 2010; 54: 10.3402.

- Gootman E. Weight Watchers Upends Its Points System. The New York Times, 3 December. 2010. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/04/nyregion/04watchers.html.

- Fletcher D. A Brief History of Fad Diets. Time, 15 December 2009. Available at http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1947605,00.html.

- Wrangham RW. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York: Basic Books, 2009.

- Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. The Lancet 2011; 377(9765): 557-567.

Please cite as: Barr S. When calories are not calories. [Short communication] World Nutrition, March 2011, 2, 3: 154-157 Obtainable at www.wphna.org

Letters

Give us this day – or not?

Editor's comment. The first letter below is from Lluis Serra-Majem, president of the Mediterranean Diet Foundation. He was prime mover of the 1st and 2nd World Congresses on Public Health Nutrition, held in Barcelona in 2006 and Porto in 2010. Through his energy and enterprise, and that of many colleagues, the Mediterranean Diet is now a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Of Humanity. His letter is followed by responses from Carlos Monteiro and Geoffrey Cannon

Please, don't go breaking my bread

Sir: I was somewhat disconcerted by the critical remarks made by Carlos Monteiro in his 'ultra-processing' commentary (WN January), about bread and sandwiches.

Bread is one of the core elements of the Mediterranean diet. Its nutritional importance has been documented in numerous studies and treatises. It is an important source of carbohydrates, proteins, fibre, vitamins and minerals, which contribute to meeting our daily nutrient requirements. Moreover, its cultural and gastronomic importance has also come to light throughout the unfolding of history.

Nonetheless, bread has received unfair treatment from certain pseudoscientific sectors. It is a food that is reviled by some but also loved, sometimes secretly, by the immense majority. And it will take time and considerable effort for bread to regain the place that it has historically occupied. One of the key objectives of nutrition education should take on repositioning and revaluing bread once again as a protagonist of our daily diet.

Who doesn´t close their eyes upon smelling freshly baked bread, and dream of uncountable memories and experiences, in which hot bread was offered to us, as an almost sacred and pure food, by our mothers? Who doesn't long for a piece of bread dipped in extra-virgin olive oil, or a crusty loaf containing a tasty filling? At any point within our Mediterranean geography you can find a good baker waking up at dawn every day of the year, so that upon getting up, we can enjoy a lovely piece of bread for breakfast.

In Catalonia we have pa amb tomaquet, a rustic crusty bread with garlic, tomato, a pinch of salt and quality virgin olive oil – a marvel which defies description. And how many different sandwiches have we eaten? In Spain, we should make a monument to the sandwich containing ham, tomato, tuna or squid, or else including omelette, or salad, pork, or sardines, or marmalade, or else with mortadella, or oil, cheese, or with honey or chocolate. My grandmother used to put sugar and wine on bread! We can enjoy multitudes of sandwiches for breakfast, as snacks, or even comprising lunch or dinner.

Is there anything that is more balanced from a nutritional point of view than a great sandwich? We know that it's the best that we can give to our children. Even so, we often succumb to easier options that, without a doubt and on many occasions, are less healthy and almost always less tasty. Is this a consequence of the recommendations – in line with Carlos Monteiro's views, or those of Dr Atkins's so-called Diet Revolution – to cut down bread and cereals? This seems likely.

During the 1960s in Spain, when the Mediterranean diet was still in good form, the daily per capita consumption of bread was around 300 grams. These were the times when obesity didn't exist; perhaps you would see a token 'fat' or 'chubby' person. We had a traditional diet based on a thousand year-old culture emerging from the land and the sea, reflected in its landscapes and customs.

Now, fifty years later, daily mean bread consumption hardly reaches 80 grams, and our children are among the most obese in Europe. Some years ago the traditional dishes we ate on special occasions, and our cuisine, have become simplified to unsuspected levels. Moreover, portion sizes, often for dishes that are of high energy density, greatly surpass our energy needs. This scenario combines with altered ways of life, in which physical activity and thus energy expenditure are low. And yet we are still being sold the message that bread is fattening, although there are very few antecedents in nutrition where a claim has been made with so little – if not null – scientific evidence to endorse it.

On the other hand, sound documentation, derived from epidemiological as well as from intervention studies, clearly indicate that an adequate consumption of bread and cereals (especially in the form of wholegrains) is associated with decreased risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, and certain inflammatory pathologies, including intestinal diseases.

I do agree with Carlos Monteiro on the point that the quality of bread production has gone downhill. The use of poor quality flour, frozen dough and rapid baking processes have led to bread being offered at ubiquitous points of sale (supermarkets, petrol stations, and so on) and not in traditional bakeries or bread shops. A certain amount of evidence exists affirming that the flour of artisanal bread dough has a lower glycaemic load and index, and as such, bread made with such dough is perfectly suitable for a balanced diet. It's somewhat similar to what happens with pasta, which has distinct nutritional characteristics when it's boiled a lot versus being prepared al dente.

But the bread that I speak of, always in the context of the Mediterranean diet, now part of UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, surely is not the same bread that Carlos Monteiro has tried in Brazil. My bread consists of high-quality starter dough, followed by an unhurried process of artisanal elaboration. It's clear that the issue of bread needs our dedicated time and much attention (and less frivolity), at least in the Mediterranean Basin, so as to regain and reposition it as having a greater place in our daily diets.

Shouldn't the World Public Health Association be engaged in defending and protecting culinary traditions, and not in opposing the consumption of those foods that have suffered the erosion of industrialisation? And a suggestion to Carlos Monteiro: can we not go back to eating artisanal bread, even though it might be defined as 'ultra-processed'? It is our hope that this occurs, for the good of our public health and our culinary and gastronomic cultural heritage.

Please, don't go breaking my bread!

Lluis Serra-Majem

President, Mediterranean Diet Foundation

Parc Cientific de Barcelona

Baldiri Reixac, 4-8, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

Biography posted at www.wphna.org

www.fdmed.org

Email: lserra@dcc.ulpgc.es

Please cite as: Serra-Majem L. Please, don't go breaking my bread. [Letter] World Nutrition, March 2011, 2, 3: 157-160. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

Please, don't change my words

Carlos Monteiro replies:

Sir: As is known to readers, I am writing a series of commentaries for WN on the importance of food processing for public health. Their main thesis is that when considering food, nutrition and public health, the key factor is not nutrients, and not particular foods, so much as what is done to foodstuffs and the nutrients originally contained in them, before they are purchased and consumed. That is, the big issue is food processing – to be more precise, the nature, extent and purpose of processing.

Specifically, the big public health problem is the increasing worldwide consumption of ready-to-eat or ready-to-heat ultra-processed products (such as breads, burgers, nuggets, chips (crisps), 'instant noodles', sugared cereals, 'cereal bars', and an uncountable number of packaged snacks and desserts). This is paralleled by the displacement of proper meals prepared with unprocessed or minimally processed foods (such as whole grains, meat, milk, vegetables, and fruits) with the use of culinary ingredients (such as vegetable oils, flours, and sugar).

In his letter, Lluis Serra-Majem does not address the central subject of my commentaries, which is the link between food processing and public health. He starts by saying he was disconcerted by the critical remarks made in my January commentary about bread and sandwiches. He then says:

- Bread is an essential part of the Mediterranean diet. Correct.

- A piece of freshly baked bread is irresistible, particularly if dipped in extra- virgin olive oil. Correct for him and for most people living in Mediterranean countries or raised in families with Mediterranean antecedents (including myself).

- There is no food 'more balanced from a nutritional point of view than a great sandwich' which is 'the best that we can give to our children'. Without references, this looks like a joke!

- An adequate consumption of bread and wholegrain cereals is associated with decreased risk of chronic diseases. As repeated in my commentaries, it does not make sense to consider whole grains (minimally processed foods) and bread (a ultra-processed product) as belonging in one single food group.

The letter also couples my views with those of the Atkins diet, implying a recommendation to cut down bread and also grains (cereals). At this point, I started to wonder if Lluis Serra-Majem has really been paying attention to what I wrote. As I repeatedly state, breads and grains belong to different basic groups, when the nature and extent of processing is taken into account. The Atkins proposition is based on the nutrient composition of foods (in this case, proportion of carbohydrates) and has nothing to do with my views. My views on the Atkins diet can be checked in my February commentary.

Furthermore, I do not recommend that ultra-processed products should never be consumed. Nor have I said that any specific ultra-processed product should be cut out of diets. In general, in most countries now, far too much of such products are consumed. One of the tasks of the group working on this issue is to estimate reasonable upper limits for consumption – and production – of ultra-processed products, taking into account reliable data from various countries. It is very unlikely that any of our evidence-based recommendations will imply reduction of current levels of production and consumption of freshly baked artisanal bread, Unfortunately this is now an 'endangered species' in the Mediterranean region and elsewhere.

Lluis Serra-Majem wonders what sort of bread I eat. The city of São Paulo, where I live, is probably as rich in gastronomic delights as any great city in the world, in part because of its rich mix of people originally from the entire Mediterranean littoral, and also from Africa and Japan, as well as from all Brazilian states. When I eat bread, which sometimes I do, it is similar to the bread Lluis Serra-Majem celebrates, delicious eaten by itself, or as dipped into the juices of fish or meat dishes.

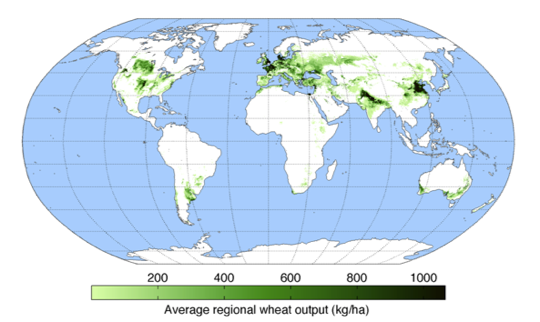

But here is a warning note to evangelists for the Mediterranean diet. See the map above, of wheat-producing countries. Wheat, from which almost all bread is made, is not native to Brazil or to Latin America. Some is now grown in southern Brazil, as the map indicates, but this is a recent phenomenon. Our indigenous and established starchy crops are manioc (cassava), corn, and rice. Gourmet bread here is as good as I have eaten anywhere. But the mass-produced bread that is sold and consumed everywhere in Brazil now, made as elsewhere in the world with flour from just a few strains of wheat, is at least as disgusting as that which now dominates the bread market in wheat-producing and other wheat-importing countries.

With very many colleagues committed to public health nutrition in its social and environmental as well as biological aspects, I am opposed to the promotion of bread in countries with no tradition of wheat. Let's be very careful not to get starry-eyed about bread, or indeed other wheat products, most of all in parts of the world whose food cultures are based on other grains, or on roots and tubers, such as Africa and Latin America, much of southern Asia, and the Pacific region. This issue is social, cultural, economic and environmental, as well as biological. Let's not blindly assume that the Mediterranean diet is a good export.

Please, don't change my words.

Carlos Monteiro

Centre for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition

University of São Paulo, Brazil

Biography posted at www.wphna.org

Email: carlosam@usp.br

Please cite as: Monteiro C. Please, don't change my words. [Letter] World Nutrition, February 2011, 2, 3: 160-161. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

Please, esteemed colleagues...

Geoffrey Cannon adds:

Sir: ... is not a possible beginning here, for I am editing these pages! Readers will I hope accept a note from me as an interested and engaged reader.

Here above is a picture of a type of bread Lluis Serra-Majem celebrates, and which Carlos Monteiro occasionally enjoys. The picture is taken from UNESCO's website. It is there used as an illustration of the splendid and successful bid by Spain, Italy, Greece and Morocco, to have 'the Mediterranean diet' accepted as a UNICEF 'intangible cultural heritage of humanity'. I put the term 'Mediterranean diet' in quotes, because there are a number of discrete traditional diets in different regions of the Mediterranean littoral, some of which, like those of the African and Asian Islamic countries, have much in common with those of the southernmost European countries, but also much that is different (1). For example, not all include wheat and its products.

I wonder what percentage of the bread now produced and consumed in Mediterranean countries is of this type – artisanal, made with locally milled flour from locally grown wheat, baked and eaten fresh every day, delicious by itself? Lluis Serra-Majem and his team may have the figures. My guess is on any national basis now, less than 3 per cent (2).

Now here above is a picture of the type of bread that dominates the market in wheat-producing and many wheat-importing countries, including France, Spain, Italy and Greece. It is degraded and disgusting. It has no place in the 'Mediterranean diet' and no significant place in any healthy diet. But bread – which in practice almost always means this stuff – is recommended to be consumed abundantly in official and other authoritative dietary guidelines, and 'Food Guide Pyramids', throughout the world – and Lluis Serra-Majem seems to be repeating this error.

The team working with Carlos Monteiro to classify foods, ingredients and products, as shown in the first WN commentary last November, spent some time discussing the fact that the same word is used to identify foods or products that actually are different, in various aspects. 'Meat' is an example. There are big differences between meat from wild animals, and meat from industrially produced animals – and birds and fish, too. Comparably, there are substantial differences between wholegrain rice, parboiled rice, and white rice. The same point applies to bread, as the two pictures above illustrate. A case can be made for using – meaning inventing – different words and phrases, to indicate the differences. As I sense Carlos Monteiro and Lluis Serra-Majem agree, these differences are social, economic, historical, cultural, and environmental also (3-5). But the team decided, I am sure correctly, to keep things simple and to limit the main groupings to three.

As a personal note, in early discussions with Carlos Monteiro and his other colleagues, I resisted the idea that bread is rightly classed as 'ultra-processed'. The case for this classification, in the terms specified, is complete. But I had been recommending increased consumption of wholegrain bread for 25 years. Denis Burkitt and Hugh Trowell (6) were mentors and also friends in their later years. Denis always made clear that wholegrain bread is superior, but as a pragmatist, also felt that increased consumption of bread in general, maybe with added bran, was also sensible. This is more or less what official dietary guidelines have stated, dating back to the late 1970s (7). They have also tended to recommend more starchy foods, usually with somewhat cursory references to quality. With some uneasiness, I toed the line.

What finally made me see the light, as well as the points made above, and by Carlos Monteiro, are the facts that bread by itself is fairly energy-dense, and – surely an overwhelming point – that almost all bread now produced and consumed is palatable only as a vehicle for what are usually fatty or sugary and often also salty spreads, fillings or toppings. Lluis Serra-Majem is quite right to say that the sandwiches he has relished all his life are delicious and nourishing. But let's get real. Such gourmet delights are not what most people buy in snack bars or make at home.

Bread is rarely a good staple food, and the only bread worth eating is that which is good to eat by itself. Further, as Carlos Monteiro says, bread and wheat products should not be promoted in parts of the world where other grains, or roots or tubers, are the main starchy staples. As soon as I realised this, much about nutrition and public health that had remained hazy for me, became clear.

When the time comes to publish complete specifications and detailed recommendations, Lluis Serra-Majem and other champions of high-quality bread can I think be assured that this will be distinguished from plastic bread. On the whole, leaving aside rash statements such as unqualified phrase of any kind of bread and sandwiches, it seems to me that Lluis Serra-Majem is on the same side as Carlos Monteiro.

So please, esteemed colleagues...

Geoffrey Cannon

World Public Health Nutrition Association

Rio de Janeiro

Biography posted at www.wphna.org

Email: GeoffreyCannon@aol.com

References

- Roden C. A Book of Middle Eastern Food. London: Penguin, 1970.

- Da Silva R, Bach-Faig A, Quintana B. Buckland G, Vaz de Almeida M, Serra- Majem L. Worldwide variation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, in 1961-1965 and 2000-2003. Public Health Nutrition 12, 9(A): 1676-1684.

- Jacob H. Six Thousand Years of Bread. Its Holy and Unholy History. Garden City NY: The Lyons Press, 1997. First published 1944.

- David E. English Bread and Yeast Cookery. London: Allen Lane, 1977.

- Bateman M, Maisner H. The Sunday Times Book of Real Bread. New York: Rodale Press, 1982.

- Trowell H, Burkitt D, Heaton K (eds) Dietary Fibre, Fibre-Depleted Foods and Disease. London: Academic Press, 1985.

- Cannon G. Food and Health: the Experts Agree. An analysis of one hundred authoritative scientific reports on food, nutrition and public health published throughout the world in thirty years, between 1961 and 1991. London: Consumers' Association, 1992.

Acknowledgement and request

As well as editing WN, I am a member of the team working with Carlos Monteiro on the project whose products include the series of WN commentaries on ultra-processing.

Please cite as: Cannon G. Please, esteemed colleagues... [Letter] World Nutrition, February 2011, 2, 3: 162-165. Obtainable at www.wphna.org