2011 October blog

Geoffrey Cannon

Juiz de Fora, Brazil. One of the forces Robert Kennedy denounced, in his 1968 run for the US presidency, is that which equates progress with econometric growth, as measured by gross national product. He exposed the illusion that the more any nation gets and spends – the more money its institutions and people turn over – the greater its achievement and general well-being. He did so in a speech quoted at the end of this column. But surely we now see that the human species can survive and thrive only if it consumes less and conserves more. Treading less heavily on the planet, now obviously essential, means that gross (an apt word) national products need to decrease. This insight should guide all public policies and actions, including those concerning health and nutrition. That's why Robert Kennedy, flawed though he was, is this month's hero.

The message is now beginning to get across. This summer Niu Wenyuan, chief scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and advisor to the Chinese national cabinet, launched a new gauge of development based on equity, sustainability, and ecological impact (1). Last month Jeffrey Sachs, the US economist who did as much as anybody to push privatisation and the demolition of public goods including public health capacity in Bolivia, Poland and Russia (2), wrote in a column published in many journals throughout the world: 'In the US, gross national product has risen sharply in the past 40 years, but happiness has not. Instead, single-minded pursuit of GNP has led to great inequalities of wealth and power, fuelled the growth of a vast underclass, trapped millions of children in poverty, and caused serious environmental degradation' (3).

This month I begin with a fairly short light item. Recent research suggests that you can trust snake oil if the salesman is Chinese and the fish can swim. After that, and before coming back to Robert Kennedy, here is the third of my four-part series on the 1970s-1990s 'food movement' in the UK: the story of 'the food scandal', in which I played a part, and that of 'The Bovril Two', of whom I was one.

References

- Watts J. Chinese green economist stirring a shift away from GDP. The Guardian, 16 September 2011.

- Klein N. The new doctor shock [Chapter 7]. The capitalist Id. [Chapter 12]. In: The Shock Doctrine. The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Picador, 2007

- Sachs J. America and the pursuit of happiness. Gulf Times, 1 September 2011.

Snake oil. Inflammation, intelligence

The snakes must swim

Original Chinese remedies using oil from aquatic snakes probably worked. Liniments that used rattler oil – or rubbish – earned salesmen a bad name

Lately I have been neglecting my pledge to include short light items – journalists call these 'squibs'. One type I enjoyed when young was 'Ripley's Believe it or Not', an illustrated strip which still runs in US newspapers, showing phenomena like toads that rain from the sky, a ship sunk by a meteor, or a mother of 30 children, claimed to be true. Was there a Ripley on snake oil? 'Snake oil salesman' (see pictures above, centre and left) has since Wild West days meant a fraud who persuades credulous folks that his worthless nostrum is a genuine remedy. By extension, the term is also used of industrialists and politicians seen as crooks or charlatans, or anybody trying to 'sell a line'.

So here comes my jumping jack. It's got everything: premature death, a reputation trashed, and mass medical fraud.

In April 2003 two obituaries of David Horrobin, the scientist and entrepreneur who championed and manufactured evening primrose oil, appeared in The Independent (1) and the British Medical Journal. They were strange virulent demolition jobs. The BMJ then ran over 125 pages of on-line rapid responses, almost all denouncing the obituary (2). What caused special anger was the punch-line that David Horrobin 'may prove to be the greatest snake oil salesman of his age'.

This made me think. Snake oil... evening primrose oil.... As all nutrition students know, evening primroses contain the omega-6 unsaturated gamma-linolenic fatty acid. What about snakes? Rattlesnakes, whose oil is advertised as the elixir to cure all sorts of ailments in the picture above left, contain the omega-3 unsaturated eicosapentanoic (EPA) fatty acid. Both are lacking in industrialised food supplies and thus diets.

Curiously, the folk medicine claims made for snake oil were rather like those made by manufacturers (like David Horrobin's firm Efamol) for evening primrose oil – good treatment for inflammatory conditions like arthritis and bursitis, and also for mental conditions like depression. The general claim was in effect that they oiled bodily systems, including joints and nerves, that otherwise, especially if overused, might well seize up. But rattlers, or any other ground snakes, don't contain much EPA. Besides, the nostrums labelled as snake oil offered at travelling medicine shows as cure-alls, no doubt were often mainly made up from any cheap stuff at hand that had an impressively horrible smell and taste.

However! Here comes the Ripley bit! The original snake oil medicine available in the Wild West as from the California gold rush in the mid-19th century, was imported from China for the use of the myriads of Chinese people who came to the US to work in the mines and on the railways, and also to start their own enterprises. Chinese pharmacists knew that their snake oil worked. This was not made from rattler oil. No, sirree! It used the oil of water snakes, as shown in the picture above right, whose fat is 20 per cent EPA, as compared with 18 per cent from salmon and a paltry 8.5 per cent from rattlers.

This makes sense. The fat of cold-blooded animals has to remain liquid in all temperatures, otherwise they would not be able to swim. And guess what! Orthodox tests on animal models are showing that water snake oil actually does relieve inflammation, and also may have cardiovascular benefits. Neurological too – rats dosed with water snake oil whizz through mazes(3). So if David Horrobin really had been a snake oil salesman he might have earned an epic reputation – always provided that his snakes could swim.

References

- Richmond C. David Horrobin. Champion of evening primrose oil. [Obituary]. The Independent, 17 April 2003.

- Cannon G. Man is not a rat, and other items. [Out of the Box]. Public Health Nutrition 2003; 6(5): 427-329.

- Graber C. Snake oil salesmen were on to something. Scientific American, 1 November 2007.

History. Policy. The Food Scandal

This great movement of ours? (3)

Access the July story of the Coronary Prevention Group hereAccess the August story of the NACNE report revelation here

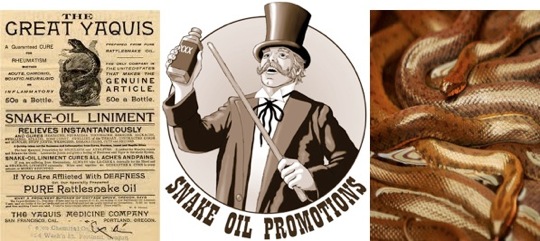

This month I summarise what became known in the UK as 'the food scandal', in which I was heavily involved. Its period was between 1984, when the book with this title was first published (1), until 1985-1986, when BBCtv completed a total of 48 nationally networked programmes within half a dozen series, many in prime time, under its Food and Health Campaign banner, which also engaged BBC Radio. It's not immediately obvious why events in the UK of a quarter a century ago are relevant to us today. But the story resonates with some current affairs, and there are some lessons and warnings that may be helpful to us now, which are at the end of this item.

The Food Scandal

The Food Scandal: the publisher (Gail Rebuck), the publication (the 1985 paperback edition), the product (Bovril), the prosecution (the High Court)

In the second half of the last century, the authorities in the UK were slow to see that chronic diseases, notably coronary heart disease, had replaced infectious and deficiency diseases as massive public health problems. They were also slow to notice that the nature of the national food supply had changed dramatically. There was certainly little inclination to connect these two phenomena. People in authority, like everybody, tend to get set in their ways. This story also sounds strangely familiar now, with the parallel rises in production by transnationals of energy-dense ultra-processed products, and of what is now pandemic overweight and obesity.

But in the 1960s and 1970s, and into the 1980s, there was a specific problem with democracy in the UK. During the two world wars, the UK necessarily had become in many respects totalitarian. Its economy, including its food systems and supplies, was controlled by leaders in government and industry, with their expert advisors, meeting in secret. Into the 1980s, not a lot changed. The main health imperative was what we now call food security: to ensure that practically everybody always had plenty to eat, measured in terms of dietary energy – calories.

The increasingly mechanised and concentrated agriculture and food manufacturing industries delivered these goods. The system worked. For these and other reasons, UK legislators and civil servants retained a collusive relationship with big business and associated experts. They shared what would now be seen as a naive belief in the benefits of food technology and processing. They resisted the idea that heart disease, which had rapidly become epidemic in high-income industrialised countries, was in any way connected with the national food supply, which had in parallel rapidly become more processed, fattier as well as sugary – and also more energy-dense (2). Yes, these issues have an uncanny resonance with our times now.

In my July column I told the story of how a group of courageous cardiologists and activists forced the issue of heart disease and its preventability on to the UK national agenda, between 1976 and the early 1980s. In my August column I told of how suppression by the UK government, with industry support, of firm evidence on food, nutrition and chronic diseases, recorded in what became known as the NACNE report (3), was exposed (1,4). As a result, a vast number of media stories identified heart disease, and also obesity, as preventable, in large part by healthy diets, with all this implied for industry policies and practices. Food and health became political. Many of these stories demonised government and industry as enemies of public health, almost by analogy with cigarette smoking and the tobacco industry. This was a shock for people in government and industry who believed they were guardians of public health and public benefactors. Rapidly – as my story this month illustrates – intense antagonism was generated.

What's in a name

What exactly did the NACNE report say, and what were the implications of its recommendations? What is a healthy diet? How can customers and consumers reduce their risk of disease? What can be done to support them in their choices? Could all this be explained in clear language that could be understood and acted on by anybody? Caroline Walker, the nutritionist who was secretary of the expert group responsible for the report, was constantly asked such questions after the NACNE report was revealed in July 1983 and finally published that October, as was I, and she wrote a paper for the Lancet on the topic (5). Caroline and I decided to team up and write a plain language guide. Later that year, we responded to the invitation of Bedford Square Press, the publishing arm of the National Council for Voluntary Organisations. Would we write a ground-breaking, hard-hitting book, to spearhead the NCVO's new healthy food initiative? Sure we would, and we set to work.

My job was to write an introduction, to translate the NACNE report from scientific to ordinary language, and to write one section. While I moaned and groaned over this task, Caroline averaged 2,500 words a day. It was like she was writing a letter to a friend. We submitted the text at the end of January. The publisher replied, regretting that it was 'ultra vires our governing instrument'. We went to see him, and he spoke of 'imputations of states of mind', 'didn't commission a campaigning book', and so on. Walking down the stairs to the street, I spotted a familiar face among the framed pictures of chairmen of the NCVO board of trustees – John Partridge, the boss of Imperial Tobacco, cigarette in hand. I asked to see the current annual report, and among many others there were thanks to donors Tate & Lyle, British Sugar, and Cadbury Schweppes. Ah. Aha. This is not to suggest that any NCVO trustees or donors knew anything about this – I'm sure they didn't. We cancelled the contract. We didn't return the advance on royalties, because we hadn't been given one.

Why are we doing this for free anyway, I asked Caroline. Let's ask my publisher if she's interested. This was Gail Rebuck, then editorial director of the new firm Century, now chair and chief executive of the Random House group of publishers (pictured left, above). We went to see her on 2 March. Of course we'll publish your book, she said (6). She made two typically incisive interventions. First, she insisted that there be more positive advice. Then, what about the title itself? Our original thought was something like 'Diet, nutrition and health'. But 'diet' was no good, for most people it means slimming. 'Nutrition' was no good, it still suggested things like hospital food for patients with kidney disease, or iron supplements. 'Health' was a problem, because then as now, it had become code for 'disease' – as in Ministry of Health. We felt stuck. We gloomily agreed the dull working title, 'Food and Health'. Gail said she'd think about it.

The next week I had been invited as from The Times, by then my main national newspaper outlet, as one of a plane-load of journalists paid for by the Flora Project for Heart Disease Prevention, to attend a vast meeting of the American Heart Association in Tampa. This allowed the joke that suddenly Florida had become Flora with an added 'id' (7). Late one evening the phone rang in my hotel bedroom. It was Gail. 'I've got it', she said. 'The Food Scandal'. Indeed she had. The title had substance and it also had sizzle. A week later, back in London, on 14 March, I went to see her, and lo, she had proofs of the book jacket (second from the left, above). Very impressive. We were, we felt, on a roll.

On 23 March we delivered the final amended and corrected typescript, which the next week was read by a specialist lawyer to ensure it contained nothing defamatory. In mid-April the first bound copies were ready. On 28 April first serial rights were sold to The Times, whose news features editor Nick Wapshott agreed that it would be unimaginative just to run extracts. Instead I wrote three features each of 2,500 words, with spectacular graphics commissioned by art editor David Driver (8).

The second feature, with the title 'The cover-up that kills' focused on industry. A big diagram showed how food and drink processors protected their interests by reciprocated links with government, health professionals, and the media and sport. The sugar, fat and processed cereal industries, including companies and trade associations, were shown in the centre of the power nexus with, right in the very centre, the 'sweet fat' industry, including the Food Manufacturers Federation, the Food and Drink Industries Council, the Cocoa, Chocolate and Confectionery Alliance, the Cake and Biscuit Alliance, and a couple of firms as illustrations – Mars, and Cadbury Schweppes. Again, this all has an uncanny resonance with current affairs now.

The book was published on 11 June. The Times advertised the features on national television on 9 and 10 June, and they ran on 11, 12 and 13 June. Then I got a call from Leon Pilpel, the correspondence editor. He told me that he had received a deluge of letters, many hostile, of which most puzzled him, and could I come in and advise him? So I did. What about these professors, he asked. He was not referring to Jerry Morris or Thomas McKeown, or others whose letters supported the general message of the features, and which were published. It's this lot, he said. He asked me to read a pile of letters. Have you noticed, I said, the recurrence of the same witty phrase, 'in which Mr Cannon reviews his own book'? Yes, he said, exactly – who are these guys, do you know? Oh yes, I said, they are food scientists and technologists, some from industry, others friendly with industry, some full-time academics, others with visiting professorships at university departments set up or funded by industry. They are writing from a common script. As I thought, he said. He published a total of around 30 letters, some kind of record for responses on one topic.

The Bovril Two

That same week we and our publishers received a statement of claim, commonly known as a writ, from Beecham, the big drug, food, drink, hair-cream and toothpaste manufacturers (9). On page 125, in the chapter on sugar, we had pointed out that most sugar that is consumed, is contained sweet processed foods, but there is some even in savoury foods, such as, in a list of 23, baked beans, cornflakes, macaroni cheese, beefburgers – and Bovril (see the classic advertisement pictured above) then manufactured by Beecham (10). We met our publisher's solicitor and advocate, who explained that Beecham was going for an injunction, meaning that if they won in court, our book would be withdrawn from sale – in effect banned. But, they said, all we have to do is to state that we will defend against any further action brought against us, and the injunction cannot succeed. Oh good, OK, we said.

On 28 June we were in the High Court, before Judge Israel Finestein. In his summary he said 'In my view the matters complained of by the Plaintiffs are such that an award of damages would not in the event be likely to be sufficient. I am bound to say that I share the great doubts expressed by Mr Bowcher' (the QC appearing for Bovril) (11) 'of the Defendants meeting damages if the Plaintiffs succeed at trial'. He granted the injunction. Outside the court our lawyer was exasperated. That's impossible, he said, the judge was wrong to do that. But it was possible, and he did do it, we said. What now? Well, he said gloomily, we could appeal. But it would cost you. How much? He guessed a sum equivalent now to around $US 75,000-150,000.

Meanwhile the book had been climbing the best-seller charts. On 21 June it was #4, on 29 June it was #3, and on 8 July it made history. In The Sunday Times best-seller charts it was #1, the top best-seller, but with an asterisk, referring to a footnote saying 'withdrawn'. Top of the charts and banned, at the same time! Thus it was that Caroline and I become The Bovril Two.

The tide turns

Thus it also was that the British manufacturers of ultra-processed products recovered their mojo. When did the tide begin to flow away from us? On Thursday 28 June 1984. Meanwhile, Gail Rebuck and her colleagues were wonderful. The Food Scandal was reissued in its de-Bovrilised edition, and we published an enlarged revised and updated paperback edition the next year (1). Gail commissioned my own next book, The Politics of Food (12).

Caroline had been planning the BBC Food and Health Campaign with colleagues in BBC tv and Radio since 1983. In 1985-1986 BBC2 and then BBC1 broadcast a four-part series, 'O'Donnell Investigates the Food Connection'; BBC2 broadcast 'The Taste of Health' eight-part series; BBC1 repeated the 'Plague of Hearts' five-part series; 'You Are What You Eat' was a six-parter on BBC1; 'O'Donnell Investigates the Food Business' was a six-parter on BBC1; and 'Go For It' was a 13-parter on BBC1. With repeats that was 48 programmes just on BBCtv. Caroline was advisor to all these programmes, often appeared on them, and wrote accompanying booklets distributed on request to a total of well over half a million viewers.

We were also masterminding the commercial national channels, and by this time came into possession of a great deal of inside information. On Monday 7 October 1985 the flagship prime-time investigative news programme World In Action told the story of the suppression of the NACNE report, and on the Tuesday and Wednesday Thames, another national commercial channel, broadcast a prime-time two-parter on chemical food additives. Both programmes had the same scoop provided by us: a film of the manufacture of the grossly degraded and hazardous 'mechanically recovered meat'. The next April, World in Action broadcast 'The Threatened Generation' which exposed the suppression of an official report on the (appalling) diets of British schoolchildren. My popular paperback Fat to Fit (13) was published at that time, as was Additives: Your Complete Survival Guide (14), to which Caroline and I contributed, which prompted the Thames two-parter. And there was more, much more (15).

All of which may suggest that we and our friends and colleagues in 'the food movement' at that time, were having things all our own way. Not so. Every season was tougher. The tide was turning, the pendulum was swinging back. National newspapers were encouraged by food industry advisors and public relations companies to run stories attacking us as 'food police', 'food terrorists', 'food Leninists', and even once (which we enjoyed) 'food Lentilists'. After the Bovril case Caroline and I were hot stuff – often too hot to be handled.

The manufacturers, and the retailers, got a grip. In its meteoric phase, the food movement, if that is what it was, fell to earth. Our campaigns eventually were evanescent. They were replaced by more methodical work, which in Britain continues now, the story of which I tell in the final part of this series, next month.

Lessons and warnings

The Food Scandal period, and the NACNE revelation before it, did begin to make nutrition interesting again in Britain, and on the whole it has remained so. There are also lessons to learn from those times, still not well understood and acted upon.

A general lesson is that any group seeking to press for better public policy needs trusted friends associated with or in government – and indeed industry, as we did then. Also, to be effective, civil society organisations need to maintain close relations with the most influential media decision-takers.

More specifically, in matters of public policy no actor, however powerful, can be effective. Also, policies enacted by the most powerful players – government combined with industry, supported by expert advisors – may well be against the public interest. This is a lesson from the UN High Level Meeting on prevention and control of chronic diseases, held in New York last month.

At least two other actors need to be engaged, for the creation and maintenance of rational policies and effective actions, in any field. These are influential, determined professional and civil society organisations, and a well-informed communications media whose executives understand the importance of the issues. Without these, the public interest is liable not to be served, and may be betrayed.

Notes and References

- Walker C, Cannon G. The Food Scandal. What's Wrong with the British Diet and How to Put it Right. London: Century, 1984. But prefer the 1985 updated and expanded paperback edition.

- Until the 1970s, UK official dietary guidelines continued to stress the importance of foods that contained plenty of energy, and made little distinction between whole starchy food and refined sugary food. Foods containing lots of fat were also seen as healthy, especially for the growth of younger children. The paradigm remained one of ensuring food and nutrition security and adequacy.

- Health Education Council. A discussion paper on proposals for national guidelines for health education in Britain, prepared for the National Advisory Committee on Nutrition Education by an ad hoc working party under the chairmanship of Professor Philip James. London: HEC, 1983.

- Cannon G. Censored: A diet for life or death. The Sunday Times, 3 July 1983.

- Walker C. Nutrition: the changing scene. Implementing the NACNE report. 3: The new British diet. Lancet 1983; II: 1354-1358.

- Gail had published my first book, Dieting Makes You Fat, co-written with Hetty Einzig. It was in Century's very first list, and was their first title to be a #1 best-seller in the UK. So we had a good thing going. Gail is now a Dame and usually in lists of the 100 most powerful UK media folks.

- Cannon G. Lifestyle with a death knell. The Times, 30 March 1984.

- Cannon G. Food, treacherous food. The cover-up that kills. So you think you eat healthily? The Times, 11, 12, 13 June 2004.

- Beecham later merged into Smith Kline Beecham and later into Glaxo Smith Kline. Bovril is now owned by Unilever. Its formulation is different now.

- We included Bovril in the list because as then formulated, its label declared the inclusion of caramel, which we believed was a form of sugar. So it is, if you make it at home in a saucepan. But when used as an ingredient or additive in processed products, the substance named 'caramel' is different. This was the issue in court. The main products that now use the Bovil brand name, contain very small amounts of sugar, or else maltodextrin, which might or might not be classified as a type of sugar. Industry prefers to equate 'sugar' with sucrose.

- It might seem odd that a product, as distinct from a person, can be defamed, but so it goes – or went, then. Another factor that didn't help – us, that is – was that in whereas in the US the plaintiff in a defamation case has to prove their case, in the UK the defendant – us, as was – has to prove theirs.

- Cannon G. The Politics of Food. London: Century, 1987.

- Cannon G. Fat to Fit. London: Pan, 1986

- Lawrence F (editor). Additives: Your Complete Survival Guide. London: Century, 1986.

- Too much. Caroline had cancer diagnosed in 1986 and died in 1988. Was gross overwork and the strain of the Bovril case a factor? It seems likely. A fuller story of our work at the time is in Cannon G. The Good Fight. The Life and Work of Caroline Walker. London: Ebury, 1989.

Robert F Kennedy

False gods

Too much and for too long, we seem to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things. Our Gross National Product, now, is over 800 billion dollars a year, but that Gross National Product… counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts… the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. It can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans. If this is true here at home, so it is true elsewhere in the world.

Robert F Kennedy, 1925-1968

Speech at the University of Kansas, 18 March 1968

In the speech of which this is an extract, made ten weeks before his assassination, Robert Kennedy stated as you see, that in 1968 the Gross National Product of the US was $US 800 billion. It is now over $US 15 trillion. Currently the GNP of China is $US 4.6 trillion, and is projected at over $US 70 trillion in 2050, when the countries with the greatest turnover as measured by GNP will be China (way ahead), and then the US, and then India, Brazil, and Russia.

Such estimates make assumptions that may be overtaken by events, such as depletion and degradation of sources of fuel or water or soil at faster rates, or more rapid climate change, than now expected. These will make food prices soar, will increase inequity and hunger, will impede the governance of more countries, and are liable to cause series of financial crashes. It is hard to see how such apocalyptic events can be averted, because they are caused by the fixation on economic growth: a worship of false gods, rightly denounced by Robert Kennedy.

Acknowledgement and request

You are invited please to respond, comment, disagree, as you wish. Please use the response facility below. You are free to make use of the material in this column, provided you acknowledge the Association, and me please, and cite the Association’s website.

Please cite as: Cannon G. The snakes must swim, and other items. [Column] Website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association, October 2011. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

The opinions expressed in all contributions to the website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association (the Association) including its journal World Nutrition, are those of their authors. They should not be taken to be the view or policy of the Association, or of any of its affiliated or associated bodies, unless this is explicitly stated.

This column is reviewed by Fabio Gomes and Claudio Schuftan. David Horrobin and I were exact contemporaries as undergraduates at Balliol College, Oxford. Many thanks to Jerrell B Whitehead of King's College Cambridge, whose researches on the 'new food movement' for his PhD thesis prompted my series here.