World Nutrition

Volume 2, Number 10, November 2011

Journal of the World Public Health Nutrition Association

Published monthly at www.wphna.org

The Association is an affiliated body of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences For membership and for other contributions, news, columns and services, go to: www.wphna.org

Editorial: The United Nations system

Can the UN stand up for

rights, equity and justice?

Access January position paper on UN SCN here

Access October news on the NCD Alliance and NCD summit here

Access pdf of Philip James commentary on the NCD summit here

Access pdf of official paper on WHO reform here

Access pdf of GDHC position on WHO reform here

Access pdf of this editorial here

Box 1

The Association and the United Nations

Editorials published in World Nutrition do not represent an official position of the World Public Health Nutrition Association unless this is explicitly stated. Nonetheless, we can say here with confidence that Association members believe in and support the United Nations system, and the principles upon which the United Nations and its agencies are founded, including those whose mandate and work are concerned with public health and with food, agriculture, nutrition and associated fields. Many Association members are or have been executives or staff of or advisors to relevant UN agencies or the UN System Standing Committee on Nutrition. The context of appraisal of UN policies or programmes in WN and on our home pages, is commitment to the UN becoming stronger and more secure.

On 1-3 November, as this month's issue of World Nutrition first goes on-line, the World Health Organization's Executive Board, its rough equivalent to the UN Security Council, is meeting. One main item in its deliberations is the future governance and financing of WHO. The paper introducing the purpose of the meeting, WHO Reform for a Healthy Future, is available here. Its paragraphs 25-28, reproduced in Box 2, indicate what the discussion is all about. The issue is the capacity of WHO. Is it, as the UN agency mandated with responsibility for health on behalf of member states, capable of doing this job? Or has it lost its way? Or, alternatively, is it now so deprived of policy initiative and so starved of funds, that it cannot do its job, despite the undoubted ability, energy and integrity of so many of its executives and staff?

These issues are being discussed within the UN System, within WHO, and also by friends, adversaries and interested parties, with increasing urgency. The most intense phase of this crisis has been during the period between 1998 and now, when Gro Harlem Brundtland, Jong-Wook Lee, and now Margaret Chan, have been WHO directors-general. The discussions converge on two questions. Is WHO broke, and if so, can it be fixed?

The statements made by and on behalf of WHO shown in Box 2, from its briefing paper on its reform, say rather clearly that the organisation is now not able to fulfil its mandate, at least in ways that it would like and that are expected of it.

Box 2

Is WHO broke?

Below are four paragraphs from the briefing paper WHO Reform for a Healthy Future, on WHO's future financing and governance. It indicates that WHO is now in a state of crisis in the Chinese sense of the word – at a crossroads, having to make a choice between two paths.

25. WHO plays a critical role as the world's leading technical authority on health. Addressing the increasingly complex challenges of the health of populations in the twenty-first century – from persisting problems to new and emerging public health threats – requires the Organization to make changes. Continuous process improvement is a vital component of organizational excellence.

26. In taking on more and more of these challenges, WHO has, like many other

organizations, become overcommitted. At a time of financial crisis, it is underfunded and overstretched. Priority-setting has not been sufficiently strategic. The Organization's financing does not always match well with its priorities and plans.

27. Further, despite several innovations put in place over the past few years, some of the Organization's ways of working are outdated. The kind of comprehensive reform that is now proposed is critical to a renewed Organization that works efficiently, effectively, and transparently. A transformed WHO will also be more flexible, responsive, and accountable.

28. Finally, the global health community has greatly expanded, such that there are now a large number of players with overlapping roles and responsibilities. In 1948 WHO was the only global health organization; now it is one of many. This proliferation of initiatives has led to a lack of coherence in global health.

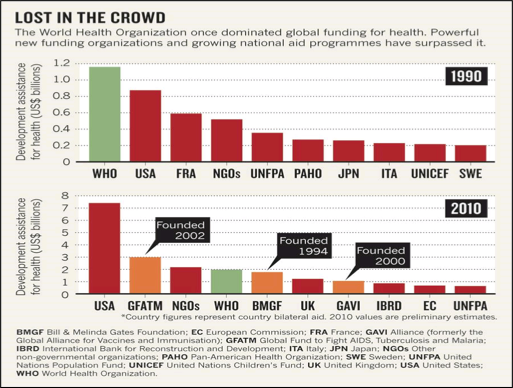

Figure 1 shows a reason why. In 1990, just 21 years ago, WHO had more funds to do its work than any single nation state, including the US, and more than all non-government organisations in its field. In 2010 the funding situation is transformed. Instead of being ranked first, WHO is in fourth position, now far below the US.

More significantly, in terms of funding it is also dwarfed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, founded in 1994, together with the GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccination and Immunization) private-public partnership, set up with Gates funding in 2000. Work on prevention and control of AIDS has since 2002 been outsourced to GFATM, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, whose main single funder is the US, also funded by the Gates Foundation. And while the World Bank does not appear in the figure, its influence in the governance and direction on world health, including food and nutrition policy, has increased exponentially in the last 20 year, as evidenced by the Bank's 2006 Repositioning Nutrition as Central to Development report, with all that flows from that.

Figure 1

World health: The main players, 1990 and 2010

So what? Few people, probably, would prefer the United Nations and its agencies, including WHO, to control global public policy. A single body of world governance, or even of co-ordination of public policy, would be vulnerable to all sorts of invidious pressures and even takeover, and any serious misjudgements or mistakes it made would be on a grand scale.

Is the UN becoming privatised?

There is some analogy here with the BBC, which until 1955 enjoyed what its founder director-general John Reith termed 'the brute force of monopoly'. Most people probably would say that on the whole, a mixed system of publicly funded and commercially funded television and radio, with many more channels, is better than one public body.

But the analogy with the BBC is not a good one. Here is why. On the one hand, the United Nations and its agencies are accountable. They are subject to the same system of governance by member states, admittedly with the distortions inevitable when a few wealthy countries provide most of the funding. Further, its various agencies do not follow any one rigid policy line. Food and nutrition is an outstanding example. A total of 19 UN agencies are involved in different ways in food or nutrition policies and programmes. The issue here is not that the UN has any monotonous voice, but rather can be cacophonous, with many policies and approaches that are at best complementary, at worst contradictory and even conflicted.

What is perhaps most worrisome about the emergence of the big new world health players, on the other hand, it is that in general, they individually and collectively have a set and rigid ideology. It may seem impolite to point out that most of them are based in the US, but this is relevant and exceptionally troublesome in this period of history. We still live at a time when official and quasi-official US institutions remain locked into a political and economic system of 'the free market', economic globalisation, belief that more money means more real wealth, under-regulated capital flow, abuse of living and natural resources, inattention to gross inequity and immiseration, and the transfer of power and influence from elected governments to transnational corporations.

Furthermore, the Gates Foundation, the most powerful player of all (1-3), which is about to become the largest single shareholder in the Coca-Cola company and in Kraft Foods (1), is as it states, 'driven by the interests and passions of the Gates family'. In practice this means that key WHO programmes are less and less in the hands of WHO itself. Instead, they are now shaped by the decisions of a gigantic philanthropy controlled by one man with his advisors, explicitly committed to the control and prevention of disease and poverty by contentious technocratic, medical-type, 'top-down' charitable approaches to public health.

The better analogy is therefore with publicly accountable public service and those commercial television networks with a blatant bias towards 'the American way'. Even more troublesome, common sense suggests that no UN agency or executive wanting to survive and prosper in the world as it is now, is likely to challenge the policies of the new philanthropies, whose directors can decide to channel billions of dollars into favoured programmes at short notice. Bill Gates himself is the only 'lay' person ever to address the WHO World Health Assembly – and twice. The reason obviously is his money and power.

Can the UN still speak for us all?

The context for these profoundly significant developments in world public health governance is the UN Global Compact, agreed in 2000. This is the most pervasive public-private partnership of them all. Set up with admirable intentions, it seeks to encourage industry to respect UN principles, such as those concerned with human rights.

But any such agreement can work well only if the public side of the partnership is strong enough to stay in control. A weakened and impoverished United Nations system is liable to be delivered into the hands of transnational corporations answerable to their bottom lines – to financial institutions and their shareholders – whose interests can only coincidentally favour the improvement and maintenance of public health and public goods. Furthermore, it is a fact that the human, material and financial resources for programmes that are co-ordinated by the United Nations and its agencies have, in the last decades, sharply diminished. Specifically in our field, the funding and staffing of UN departments and units committed to the prevention and control of disease with food and nutrition programmes, are now at scandalously low levels.

There is therefore a big question to be asked and addressed. Is the United Nations itself gradually becoming privatised? This is why friends of and believers in the UN system and principles are profoundly alarmed by the little-known moves to reform the governance of the World Health Organization. The timing is sinister.

The main concern, is that admission of partners in addition to UN member states into the governance of WHO, together with the apparent exclusion of genuine civil society organisations, seems likely to a Trojan Horse move that will pull down WHO and any other UN organisation following the same strategy. The view of the Democratising Global Health Coalition, a group of public interest civil society organisations, issued on 15 October, is stated in Box 3.

Box 3

What is the meaning of the proposed WHO reform?

In its background document for the briefing on the reform of the World Health Organization, the Democratising Global Health Coalition states as follows:

The rationale of the WHO reform has yet to be established, based on a solid in- depth situation analysis. The reform was introduced through consideration of financial difficulties and prospects for future financing of the agency. Alarmingly, as of today not one single document has been made available by the Secretariat on WHO's financing, which is the present cause of the current situation, or on present constraints, limitations of the system, opportunities for potential savings and ideas for future sustainable funding

Far beyond a managerial reform, this process is a major political and strategic move. This reform must be placed in the context of a globalised economy, the current financial crisis and the need for reasserting WHO as the leading intergovernmental agency for health.

The risk of the proposals currently put forward by the WHO Secretariat is that they undermine rather than reinforce WHO's constitutional mandate. They further dilute the right to health perspective, by opening the door to private and corporate for-profit entities to take part in policy-setting on global health. Giving more influence to private for-profit actors in international public health decision-making processes runs counter to basic democratic principles.

The unprecedented speed of the reform process, coupled with its opacity and the lack of participation by the public health community, makes it practically impossible even for Member States to follow its route with any real ownership and capacity to contribute. Yet it is precisely the Member States – the legitimate constituency of WHO – which should drive the entire process.

In addition to impairing proper governmental guidance and contributions, the current WHO reform further suffers from the exclusion of public-interest members of civil society, the ones that have taken this initiative with the serious attention it deserves. A much greater degree of public mobilisation is needed for WHO to generate the will and the consensus necessary to move forward with full legitimacy. A political dialogue on the reasons and core values steering the reform, and a broader debate involving public interest groups of civil society and public opinion are still to be seen.

Can the UN System, and WHO, stand the strain? Both are pressed on all sides by powerful forces. These include the most potent member states, and above all the transnational organisations the effect of whose business, generally speaking, includes the exploitation of human, living and natural resources, chaotic fluctuations in the cost of money and food, the evisceration of impoverished nations, the increase of inequity between and within regions and countries, the generation of climate change, and the erosion of human rights.

Such commercial forces can be characterised as Big Money, and in our field of interest, Big Pharma, Big Booze, Big Sugar, Big Snack, Big Burger and Big Soda. These are the colossal drug, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink products industries and their associates, all of which are free to move their headquarters, their capital, their factories, and their executives and staff to wherever in the world where they can have most scope, make most profit, and be most powerful. In some cases individually, these transnational corporations are more potent than most national governments; and the government that towers above all others, that of the US, remains committed to an ideology that gives corporate power a free hand. In our area of public health which includes food and nutrition policy and practice, this is intensely troublesome, because the interests of the dominant corporations are in direct conflict with those of public health and public goods.

These strong words are justified and cannot be seriously challenged. As Margaret Chan, the current WHO director-general, said at the World Conference on the Social Determinants of Health held in Rio de Janeiro last month: 'Prevention is by far the best option, and it is entirely feasible and affordable in any resource setting. But nearly all the risk factors lie out of the control of the health sector. These include junk food, tobacco, alcohol and sedentary lives. Prevention measures lie as well outside the health sector, and public health loses power in this fight. We need the right policies in place in all sectors of government'.

She went on to say: 'Vast collateral damage to health is being caused by policies made in other sectors and in the international system. Good policies are known and well studied, but putting them in place is an enormous challenge. It means pushing against powerful and pervasive commercial interests'. But the push from WHO is not as strong or consistent as it needs to be. It sounds like Margaret Chan is warning against a process occurring within as well as outside the UN system which, despite being head of WHO, she cannot control.

We are living in testing times. Decisions that affect public health now being taken, will affect the health and well-being of our children and their children. For the moment, one thing is clear. The United Nations is in need of greater authority and adequate funding from member states. Like the BBC, it remains the best value for money we have and are ever likely to have.

References

- Stuckler D., Basu S., McKee M., Global health philanthropy and institutional relationships: how should conflicts of interest be addressed? PLoS Med 8(4): e1001020. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001020

- Anon. What has the Gates Foundation done for public health? [Editorial]. The Lancet 2009; 373, 9675: 1527.

- Wiist B. Philanthropic foundations and the public health agenda. Corporation and Health Watch, 3 August 2011.

- See http://www.democratisingglobalhealth.org.

Acknowledgement and request

Readers are invited please to respond. Please use the response facility below. Readers may make use of the material in this editorial if acknowledgement is given to the Association, and WN is cited

Please cite as: Anon. The UN System. Can the UN stand up for rights, equity and justice? [Editorial] World Nutrition, November 2011, 2, 9: 508-514. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

The opinions expressed in all contributions to the website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association (the Association) including its journal World Nutrition, are those of their authors. They should not be taken to be the view or policy of the Association, or of any of its affiliated or associated bodies, unless this is explicitly stated.

Thanks are due to Remco van de Pas of the Wemos Foundation (the global health workforce alliance) and of Medicus Mundi, for the graphic on global funding for health reproduced here as Figure 1.